Why is the telecoms industry amongst the fastest-growing sectors for renewable energy PPAs?

In the last article in this series, we took the first of several deep-dives we will be taking into industry sectors which are heavily impacted by the energy transition – and which are driving demand for renewable energy power purchase agreements (PPAs) in Central & South Eastern Europe.

We started with the automotive sector. This time, we will consider a sector which, according to industry estimates, accounts for 1-2% of all energy consumed globally – and in which the PPA market is growing even faster: the telecommunications industry.

- How does the telecoms industry compare with other sectors when it comes to signing green PPAs?

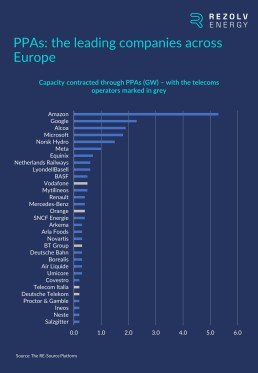

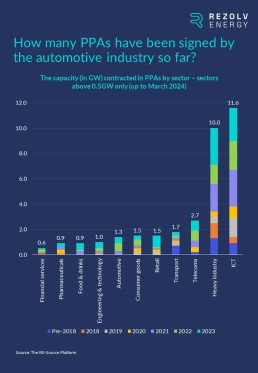

Right now, the telecoms industry sits third on the list of sectors which have contracted the most capacity through green PPAs, although it is well behind the two leading sectors on the list – ICT and heavy industry:

However, if you take ICT and heavy industry out of the equation, the telecoms industry has been the fastest-growing sector for contracting capacity via PPAs over the last five years:

- Which telecoms operators are leading the way?

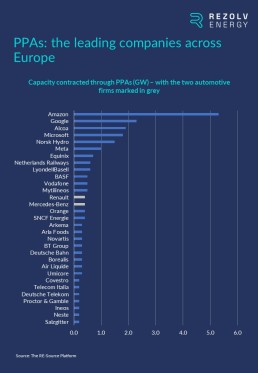

There are five telecoms operators – Vodafone, Orange, BT Group, Telecom Italia and Deutsche Telekom – in the group of 30 companies which have contracted the most clean power capacity through PPAs in Europe:

- Which companies dominate the telecoms sector in Central & South Eastern Europe?

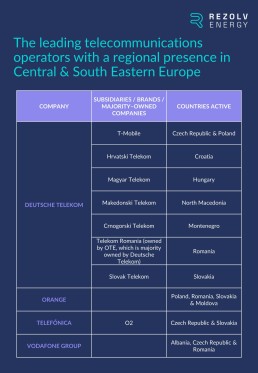

There are four telecoms operators which stand out in Central & South Eastern Europe because they have a significant presence in multiple countries across the region:

- What sustainability commitments have these companies made?

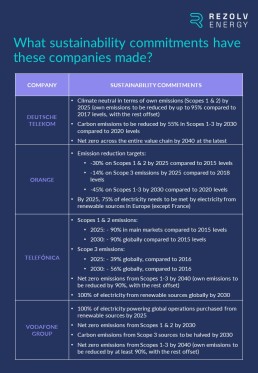

Three out of four of these companies are members of ‘RE100’, the global corporate renewable energy initiative which brings together businesses committed to 100% renewable electricity (Orange is the exception). More specifically, they have each made the following sustainability commitments:

- How is this translating into signed PPAs?

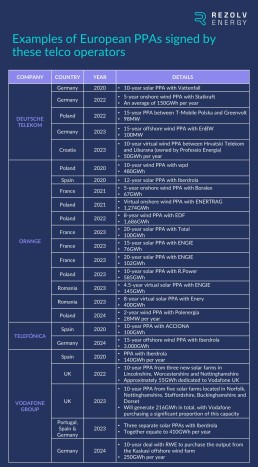

Here is an overview of the most important European PPAs signed by this group of telecoms companies:

- What is driving this interest in PPAs, and will it impact South Eastern Europe as well?

There is no question that this interest in green energy will transition into more telecoms industry PPAs being signed in South Eastern Europe. There are three main reasons for optimism:

- Telecoms operators use a lot of electricity, and decisions over renewable power cannot wait if the sector is to meet its sustainability commitments:

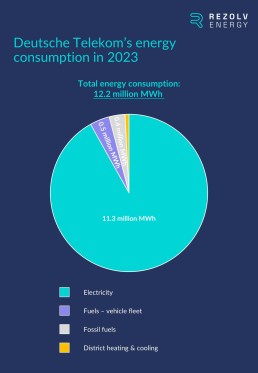

We mentioned in the previous article in this series that automobile assembly and parts manufacturing are energy-intensive processes that rely on electricity in particular. Electricity makes up an even larger share of the energy consumption mix for telecoms operators. This, for example, is how Deutsche Telekom’s energy consumption was split last year:

Telefónica’s share was even higher: electricity represented 95% of the company’s total energy consumption.

All of the major telecoms operators have made substantial efforts to reduce their energy consumption through energy efficiency initiatives, but it is not easy given that data traffic through their networks has increased so significantly over the last decade – and continues to increase. Telefónica and Deutsche Telekom have managed to reduce their total energy consumption slightly in recent years; Vodafone and Orange’s consumption has, however, continued to rise year-on-year.

Given this, the decarbonisation targets these companies have set themselves will not be achievable without renewable energy procurement at scale, and it will need to cover all subsidiaries and geographies.

- Renewable energy buying is being driven by the search for cost savings:

Procuring energy currently accounts for up to 40% of telecoms companies’ operational expenditure, and the search for cost savings helps explain the shift towards renewable energy that we have seen in recent years.

A recent article in Developing Telecoms explored this trend. In it, Enrique Dans, a Senior Fellow at the Centre for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), said this: “From my perspective, the most important factor here is cost. We are witnessing a huge decrease in the cost of renewable energy.”

The reality is that a well-structured PPA will, in the long-term, reduce a company’s energy costs compared to traditional utility rates – as well as shielding them from market fluctuations. As the telecoms industry has come to realise, there is a clear commercial rationale for signing a renewable energy PPA.

- European regulations are driving change:

Telecoms companies manage data centres which store vast amounts of information – and which also consume significant quantities of energy (a topic we will dive into in more detail later in this series).

Last month, the European Commission adopted a new delegated regulation on the first phase for establishing an EU-wide scheme to rate the sustainability of EU data centres. As foreseen under the new Energy Efficiency Directive, this secondary legislation requires data centre operators to report the KPIs to the European database by 15 September 2024, and then by 15 May in 2025 and subsequent years. With data centres estimated to account for close to 3% of EU electricity demand – a figure which is likely to significantly increase in the coming years – the scheme is intended to increase efficiency developments and to promote the use of renewable energy.

This delegated regulation is just one example of how EU legislation is steering companies towards renewable energy, but it is a particularly important one for telecoms companies and the broader ICT industry.

What is coming up next time?

Next time, we will be considering the final point above in more detail: which regulations, directives and other EU initiatives are the most important in shaping the energy buying priorities of companies across Europe? We will provide an overview…

Bekaert and Rezolv Energy sign 100 GWh wind Power Purchase Agreement in Romania

Bucharest, 4 July 2024: Rezolv Energy, the Actis-backed independent power producer in Central and Southeastern Europe, through their project subsidiary First Looks Solutions S.R.L., have signed a 10-year Virtual Power Purchase Agreement (VPPA) in Romania with Bekaert, a global leader in steel wire transformation and coating technologies. This is one of the largest PPAs ever signed in the region. The deal will see Bekaert buy 100 GWh of additional renewable power per year, reducing annual emissions by more than 41 000 tonnes of CO2e . The power will come from the 461MW ‘VIFOR’ wind farm, which has been developed by Rezolv and Low Carbon in Buzău County, Romania.

The PPA represents a new milestone in Bekaert’s Sustainability strategy “Creating a better tomorrow”. From making a positive impact with its sustainable solutions and practices, to building a diverse and inclusive future, Bekaert is determined to improve life and create value for all of its stakeholders. Through renewable energy projects like the VPPA in Romania, Bekaert increases the proportion of its renewable energy supply, reducing its carbon footprint as per its validated SBTi targets.

About the VIFOR Wind Farm

Once operational, VIFOR will be one of Europe’s largest onshore wind farms. Close to the Carpathian Mountains and benefiting from exceptional wind yields, the project will generate enough clean energy to power more than 270 000 homes and will avoid approximately 540 000 tonnes of CO2e annually. Phase 1 will install 192MW in capacity with planned expansion to 461MW in phase 2. Construction is scheduled to be completed within 18 months, with VIFOR coming onstream before the end of 2025.

In a region which has historically relied on fossil fuels for most of its energy needs, replacing fossil production with renewables delivers the maximum possible emissions reduction impact. The project will therefore play a crucial role in the region’s energy transition and support Romania in meeting its climate targets. It will also be developed to the highest international sustainability standards to ensure that it leaves a lasting, positive legacy.

Michael Hamilton, VP Commodities, Bekaert, said: “We are delighted to sign this exciting project in Romania with Rezolv. This agreement not only enhances our existing renewable energy portfolio but also exemplifies our commitment to sustainability and creating value for all of our stakeholders. By integrating renewable energy sources into our operations, we are taking significant steps towards a greener future for our company and the customers we serve.”

Alastair Hammond, CEO, Rezolv Energy, said: “We are proud to be contributing to Bekaert’s decarbonisation objectives through this VPPA. By signing it, Bekaert is also enabling the first phase of the VIFOR project, a large-scale wind farm which will play a significant role in Romania’s energy transition. Phase 2 will help us meet even more of the widespread corporate demand for clean power.”

T-Mobile Czech Republic, Slovak Telekom and CE Colo sign pioneering cross-border virtual Power Purchase Agreements with Rezolv Energy

Prague, 19 June 2024: T-Mobile Czech Republic, Slovak Telekom and CE Colo Czech Republic, all part of the Deutsche Telekom Group, have signed cross-border virtual Power Purchase Agreements (VPPAs) with Actis-backed Rezolv Energy, the Prague-headquartered renewable energy producer. These are the first cross-border VPPAs that have been signed by Czech or Slovak companies. The power will come from the 461MW ‘VIFOR’ wind farm, which has been developed by Rezolv and Low Carbon in Buzău County, Romania, with the VPPAs enabling the construction of the first phase of the project. In the second phase, a further 700GWh per year will be available for corporate buyers.

The VPPAs will see the three firms buy 100GWh of clean power per year for 12 years. T-Mobile Czech Republic has secured 50GWh per year, Slovak Telekom 40GWh per year and CE Colo Czech Republic 10GWh per year.

A Significant Milestone in Renewable Energy

The VPPAs represent a significant step forward in Central & Southeastern Europe, where most previous PPAs have been physical agreements requiring the buyer and producer to be in the same or neighbouring countries with connected grids. In contrast, a VPPA is a financial arrangement where the buyer receives certificates verifying that the energy came from a specific renewable source, with the clean power being fed into the grid.

About the VIFOR Wind Farm

Once operational, VIFOR will be one of Europe’s largest onshore wind farms. Close to the Carpathian Mountains and benefiting from exceptional wind yields, the project will generate enough clean energy to power more than 270,000 homes and will avoid approximately 540,000 tonnes of CO2e annually. Phase 1 will install 192MW in capacity with planned expansion to 461MW in Phase 2. Construction is scheduled to be completed within 18 months, with VIFOR coming onstream before the end of 2025.

In a region which has historically relied on fossil fuels for most of its energy needs, replacing fossil production with renewables delivers the maximum possible emissions reduction impact. The project will therefore play a crucial role in the region’s energy transition and support Romania in meeting its climate targets.

It will also be built to the highest international sustainability standards to ensure that it leaves a lasting, positive legacy.

Last week, finance loan facilities of up to €291 million were secured to support the Phase 1 construction from a consortium of eight lenders led by Erste Group, UniCredit Group and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, as well as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), Intesa Sanpaolo Group, OTP Bank, Raiffeisen Bank International AG and Garanti BBVA Romania.

Pavel Hadrbolec, CFO, T-Mobile Czech Republic and Slovak Telekom, said: “We are proud to became an enabler of a new renewable energy site and became a frontrunner in this area. This is a further step in our decarbonisation journey. The deal also brings us relevant risk diversification to our energy procurement strategy and energy prices hedging.”

Alastair Hammond, CEO, Rezolv Energy, said: “These are the first cross-border virtual PPAs that have been signed by Czech or Slovak companies, and they are an important signal to other businesses in these two countries. They do not need to wait for renewable energy capacity to start coming onstream in volume in their home market. These agreements will enable Phase 1 of this project, but Phase 2 will make a further 700GWh available per year. The widespread corporate demand for green electricity can therefore be met now.”

Jaroslava Korpanec, Partner, Head of Central and Eastern Europe, Energy Infrastructure at Actis, commented: “Actis launched Rezolv Energy to deliver a new era of clean, sustainable energy in Central and Southeastern Europe. This VPPA demonstrates how Rezolv is leading the CEE market, offering innovative solutions to help corporates decarbonise while meeting their energy needs. Rezolv’s renewable power projects are making a tangible difference and accelerating the energy transition in the region.”

Rezolv Energy was launched 18 months ago by Actis, a leading global investor in sustainable infrastructure, and already has well over 2GW of clean energy being prepared for construction in South Eastern Europe. As well as the VIFOR wind farm, projects include Dama Solar in western Romania which, at 1,044MW, will be the largest solar plant anywhere in Europe once it is built, the 600MW Dunarea East & West Wind Farms in Romania’s Constanța County, and St. George, a 229MW solar project in north-eastern Bulgaria.

Rezolv Energy & Low Carbon hand Vestas EPC contract for VIFOR wind farm in Romania

Bucharest, 17 June 2024: Actis-backed Rezolv Energy and Low Carbon, through their project subsidiary First Looks Solutions S.R.L., have selected Vestas as the engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) partner for the first phase of the ‘VIFOR’ wind farm in Buzău County, Romania. Phase 1 will install 192MW in capacity, with planned expansion to 461MW in Phase 2.

The first phase of the VIFOR project will involve the installation of 30 EnVentus Vestas V162 wind turbines, each with a capacity of 6.4MW. The turbines have a tower height of 166 metres and a rotor diameter of 162 metres.

Once operational, VIFOR will be one of Europe’s largest onshore wind farms. Close to the Carpathian Mountains and benefiting from exceptional wind yields, the project will generate enough clean energy to power more than 270,000 homes and will avoid approximately 540,000 tonnes of CO2e annually. The project will support Romania in meeting its climate targets and play an important role in the region’s energy transition.

Last month, the Romanian Energy Regulatory Authority (ANRE) issued the setting-up authorisation for the first phase of the VIFOR project. This was the final approval required. Construction is scheduled to be completed within 18 months, with VIFOR coming onstream before the end of 2025.

Vestas’ role as EPC partner will involve working alongside Rezolv and Low Carbon to implement the Environmental and Social Management Plan for VIFOR. Rezolv’s sustainability strategy has been built on industry best practice and aligns with international standards, including the Equator Principles and the International Finance Corporation (IFC)’s Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability. One of its pillars is striving to ensure that each of its renewable energy plants supports flourishing and sustainable ecosystems.

In addition to the environmental benefits, VIFOR will create local jobs during both the construction and operational phases, deliver economic benefits, and support community initiatives in Buzău County aimed at ensuring that the project leaves a lasting, positive legacy for local people.

Last week, finance loan facilities of up to €291 million were secured to support the Phase 1 construction from a consortium of eight lenders led by Erste Group, UniCredit Group and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, as well as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), Intesa Sanpaolo Group, OTP Bank, Raiffeisen Bank International AG and Garanti BBVA Romania. Phase 1 is also underpinned by five landmark commercial power purchase agreements (PPAs).

Alastair Hammond, CEO, Rezolv Energy, said: “The VIFOR wind farm will play a significant role in reducing Romania’s dependence on fossil fuels, enhancing the country’s energy security and improving air quality. Vestas, as the world’s largest wind turbine manufacturer and with the greatest number of MWs installed in the region, is a natural partner for this, the first large wind farm in the CEE/SEE region in the past 10 years. Crucially, Vestas also shares our commitment to the responsible and sustainable development of renewable energy projects, which made them a natural choice for VIFOR.”

Martin Langham, Managing Director at Low Carbon said: “We are delighted to reach this major milestone in the development of the VIFOR wind project, which is a result of the tireless efforts of the team and our Rezolv partners over several years. The EPC agreement with the leading wind turbine manufacturer, Vestas, will be one of the largest contracts of its kind in Europe reinforcing our track record for delivering clean energy infrastructure on this scale. Furthermore, the project will play a key role helping Romania to decarbonise its electricity grid and accelerate the energy transition in Eastern Europe.”

Nils de Baar, President of Vestas Northern and Central Europe, said: “VIFOR will become one of the largest onshore wind projects in the region, contributing significantly to Romania’s energy transition ambitions. Vestas is pleased to deliver this order as a turnkey project, and our thanks go to our partners for the great collaboration and their trust in our industry leading technology.”

Rezolv Energy was launched 18 months ago by Actis, a leading global investor in sustainable infrastructure, and already has well over 2GW of clean energy being prepared for construction in South Eastern Europe. As well as the VIFOR wind farm, projects include Dama Solar in western Romania which, at 1,044MW, will be the largest solar plant anywhere in Europe once it is built, the 600MW Dunarea East & West Wind Farms in Romania’s Constanța County, and St. George, a 229MW solar project in north-eastern Bulgaria.

Rezolv Energy & Low Carbon sign finance facilities for up to €291 million to build the VIFOR wind farm in Romania

Bucharest, 13 June: Rezolv Energy and Low Carbon, through their project subsidiary First Looks Solutions S.R.L., have secured finance loan facilities of up to €291 million to support the Phase 1 construction of the ‘VIFOR’ wind farm, a major project located in Romania.

The financing received resounding support by the financing community. The consortium of eight lenders was led by Erste Group, UniCredit Group and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, as well as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), Intesa Sanpaolo Group, OTP Bank, Raiffeisen Bank International AG and Garanti BBVA Romania.

This landmark transaction is the first financing for Rezolv Energy, which was launched 18 months ago by Actis, a leading global investor in sustainable infrastructure, to build a multi-gigawatt portfolio of onshore wind and solar parks in Central and Southeastern Europe.

Phase 1 of the VIFOR project will install 192MW in capacity underpinned by five landmark commercial power purchase agreements (PPAs). Construction is scheduled to be completed within 18 months, with the wind farm coming onstream before the end of 2025. A planned expansion to 461MW will take place in Phase 2.

Once fully operational, VIFOR, which is located in Buzău County, north-east of Bucharest, will be one of Europe’s largest onshore wind farms. Close to the Carpathian Mountains and benefiting from exceptional wind yields, the project will generate enough clean energy to power more than 270,000 homes and will avoid approximately 540,000 tonnes of CO2e annually. The project will support Romania in meeting its climate targets and play an important role in the region’s energy transition.

In approving the loans, the banks acknowledged Rezolv’s commitment to sustainability, which has been built on industry best practice and aligns with international standards, including the Equator Principles and IFC’s Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability. One of its pillars is striving to ensure that each of its renewable energy plants supports flourishing and sustainable ecosystems.

In addition to the environmental benefits, VIFOR will create local jobs both during construction and operation, deliver economic benefits to the local community, and support community initiatives in Buzău County aimed at ensuring that the project leaves a lasting, positive legacy for local people.

Alastair Hammond, CEO, Rezolv Energy, said: “We are delighted to have secured this support from such a prestigious group of supranational lending partners, regional commercial lenders and local banks. Their support is recognition of the vital role of large-scale projects like VIFOR in the energy transition in Southeastern Europe. They are also a response to our sustainability strategy, which is designed to ensure that we set a standard for the responsible development of renewable energy projects in this region which others will be inspired to follow. That was an important factor for all of the banks.”

Rezolv already has well over 2GW of clean energy being prepared for construction in Southeastern Europe. As well as the VIFOR wind farm, projects include Dama Solar in western Romania which, at 1,044MW, will be the largest solar plant anywhere in Europe once it is built, the 600MW Dunarea East & West Wind Farms in Romania’s Constanța County, and St. George, a 229MW solar project in north-eastern Bulgaria.

What is driving the interest in PPAs that we are seeing from the automotive sector?

The first few articles in this series included some analyses of individual countries in Central and South Eastern Europe – specifically, Bulgaria, Romania and the Czech Republic.

It is now time for the first of several deep-dives into industry sectors which are heavily impacted by the energy transition – and which are driving most of the demand for renewable energy power purchase agreements (PPAs) in this region. We are going to start with an industry which has become almost synonymous with Central and South Eastern Europe: the automotive sector.

- How important is the automotive industry to Central and South Eastern Europe?

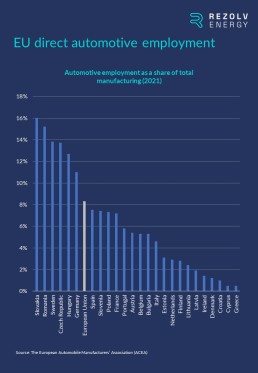

Over the last 30 years, Central and South Eastern Europe has become a key centre for automotive production in Europe – benefitting from its geographical proximity to the largest markets in Western Europe and relatively low labour costs. It continues to play an outsized role economically, with Slovakia, Romania, the Czech Republic and Hungary all in the top five countries in the EU when it comes to the proportion of jobs which are created directly by the automotive sector:

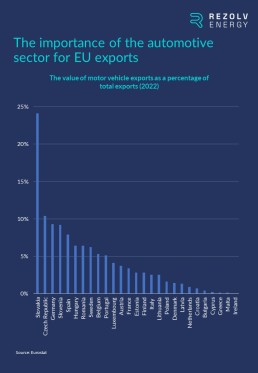

The economic value is not just in the jobs the sector supports: the industry is also a vital part of international trade in these countries. For example, motor vehicles make up almost a quarter of the total value of exports from Slovakia, and contribute a very substantial proportion in the Czech Republic (10.4%), Slovenia (9.2%), Hungary (6.4%) and Romania (6.4%) too:

- Which companies dominate the automotive sector in Central and South Eastern Europe?

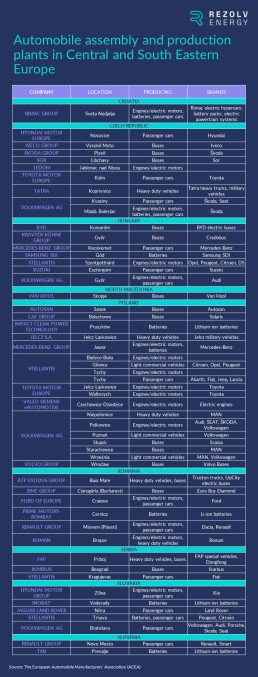

There is a long list of automotive companies with production and/or assembly plants in Central & South Eastern Europe:

The list is dominated by the biggest names in the industry – including all of the world’s top five automotive companies: Volkswagen (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia), Toyota (Czech Republic and Poland), Stellantis (Hungary, Poland, Serbia and Slovakia), the Mercedes-Benz Group (Hungary and Poland) and Ford (Romania).

However, as we explained in the last article in this series, the reason that the automotive sector contributes so much economically is not just explained by the presence of these multinational giants. It is also a consequence of the huge number of smaller local firms in their supply chains.

- What sustainability commitments have these companies made?

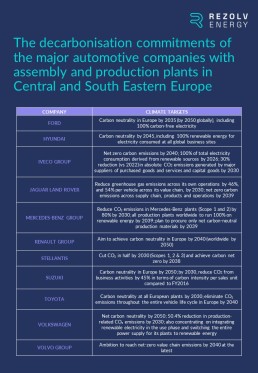

If we narrow it down and focus in on the biggest brand names from the list above (which primarily means the passenger car manufacturers), they have all committed to firm decarbonisation deadlines:

As we also explained last time, many of these targets cover ‘Scope 3’ (the entire supply chain) as well as ‘Scope 1’ (the company’s direct greenhouse gas emissions) and ‘Scope 2’ (the emissions caused indirectly through the production of the energy the company purchases / uses). This is a positive development because Scope 3 emissions represent 80% of the total environmental impact for many large companies. However, it is also a major challenge in Central and South Eastern Europe, where there are so many smaller companies supplying these multinationals. To hold on to those contracts, these businesses will need to contribute to their customers’ carbon neutrality targets by reducing their own emissions – and demonstrate that they have done so.

- Has this yet translated into automotive firms signing green PPAs?

With the transport and mobility sector accounting for about 23% of global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions, the automotive sector has been under heavy pressure to reduce its carbon footprint to comply with the Paris Climate Agreement – and, compared with other sectors, the automotive industry has set relatively stretching net zero targets.

However, despite that, the sector is lagging behind several others when it comes to the amount of capacity that has so far been contracted through green PPAs:

Indeed, at a European level, there are only two automotive companies – Renault and the Mercedes-Benz Group – in the group of 30 companies which have contracted the most clean power capacity through PPAs:

Mercedes-Benz was actually was actually amongst the very first movers on PPAs. The company signed its first PPA in 2018, agreeing to buy electricity generated at a 45MW wind farm 10 kilometres away from its manufacturing facility in Jawor, Poland. That was simultaneously the first PPA in this region and the first automotive sector PPA anywhere in Europe.

At the very beginning of 2019, Mercedes-Benz went on to sign Germany’s first corporate PPA, and, last year, two further (much larger) PPAs in its home market – for 140MW and 120MW, both wind power. In February this year, Mercedes-Benz also signed another wind PPA in Poland.

Renault, on the other hand, has preferred a mix of wind and solar PPAs. In 2021, the company signed a PPA with Iberdrola covering 100% of Renault’s electricity needs in Spain, which included the implementation of photovoltaic and wind projects at the company’s facilities. Subsequently, in November 2022, Renault announced the largest corporate PPA ever signed in France – 350MW of solar, enough to cover up to 50% of the electricity consumption of its production activities in France in 2027.

- 2024 will be the year when things start to accelerate – but what is driving the interest we are now seeing in PPAs in the automotive sector?

So far, there has been far less movement on PPAs from the automotive sector in Central and South Eastern Europe, but there have been two recent deals:

- Photon New Energy Alfa Kft signed a 20-year on-site PPA with FORVIA Clarion Hungary, a subsidiary of the automotive technology firm FORVIA, for the construction and operation of a solar PV plant on the client’s factory in Nagykáta, about 80 kilometres southeast of Budapest.

- Swiss-based Axpo signed a 10-year PPA with industrial product supplier Kolektor to buy up to 200 GWh of renewable electricity over ten years. The electricity will be used at Kolektor Mobility’s facility in Slovenia, which produces components and systems for electric vehicles.

This is an encouraging sign that things are changing, and that 2024 will be a transformative year. There are three other reasons why we are so optimistic about the outlook for this year:

- Decisions over renewable power cannot be deferred if the sector is to meet its decarbonisation commitments:

Automobile assembly and parts manufacturing are energy-intensive processes that rely on electricity in particular. This is responsible for considerable CO2 emissions which is why renewable energy procurement will need to play a central role if the major automotive companies present in this region are to meet their decarbonisation targets. Given the deadlines, these are also not decisions which can be delayed much longer.

- Automotive companies prefer PPAs:

As we have seen, PPAs in the automotive sector have really started to take off over the last three years in Europe. As a recent analysis of the PPA market in the automotive sector from SP Global concluded, “car manufacturers in the EU and US largely prefer PPAs, with green tariffs following. The automotive sector began to confidently gain momentum in the PPA market in North America and Europe. Its average annual growth in 2019-22 reached 50%, which makes it stand out compared with other manufacturing sectors.”

- Available capacity:

That same SP Global analysis made one other very important point. It said that “the rate of progress in green procurement across major car manufacturers appears to be closely dependent on…the renewable generation capacity in the region where manufacturing plants are present.”

Fortunately, renewable energy capacity is now coming onstream in volume in Central and South Eastern Europe and so, really for the first time, the energy sector can meet the corporate demand for green electricity from automotive firms.

What is coming up next time?

Next time, we will be taking another sector deep-dive – this time into the telecoms industry…

Even more urgency is required to meet the 2030 emissions targets in Central & South Eastern Europe

In the first two parts of this series, we explained why Rezolv is investing in Bulgaria and Romania. We focused on the impact that the development of renewable energy will have on emissions and human health. We also outlined why the energy transition is necessary for long-term economic competitiveness.

However, there is one other aspect we didn’t consider which is also driving change: large-scale renewable energy projects like those Rezolv is developing in Romania and Bulgaria will contribute to both countries’ climate targets.

Let’s consider Romania first. Last time, we mentioned that the percentage of electricity generated from fossil fuels in Romania dropped below 30% for the first time in 2023, with overall renewables capacity increasing from 43.1% in 2022 to 50.4%. 65% of that renewables capacity was hydropower, but we shouldn’t understate the progress that was made last year, particularly on solar power. As in Bulgaria, 2023 was the year when Romanian solar turned the corner, with over 1GW of new capacity installed, a 308% increase on 2022 – making solar PV the fastest-growing power source in the country.

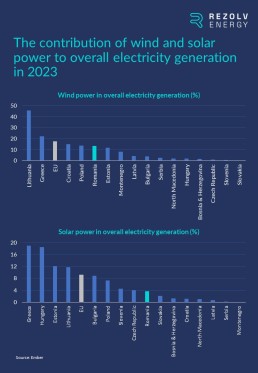

To put that into a regional context, here’s how Romania stacked up against other countries in Central & South Eastern Europe in 2023 in terms of both wind and solar capacity:

Wind capacity also increased very slightly last year in Romania – but from a much higher starting point. On both fronts, though, there is more work to do to reach the EU average, let alone catch the countries that are leading the way in the region.

Romania’s renewable energy target keeps increasing

It’s also worth considering the progress made in 2023 against Romania’s 2030 renewable energy target. The reality is that its impact was diluted by the fact that that target has been steadily increasing as the EU’s level of ambition has risen.

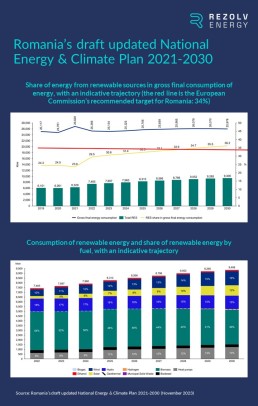

Romania’s Integrated National Energy and Climate Change Plan (NECP) for 2021-2030, which was submitted to the European Commission in 2018, set a target for the total share of renewable energy in final gross energy consumption of 27.9% by 2030.

The revised NECP, submitted in April 2020, increased that target to 30.7% – short of the Commission’s recommendation of at least 34%, but still a significant increase.

Most recently, the revised draft of the NECP that was submitted in November 2023 indicated that Romania could reach 36% by 2030 – with wind and solar the main contributors:

Attitudes are also being shaped by the renewable energy potential in the region

Romania’s increased ambition is not just a response to pressure from the European Commission: it’s also driven by Romania’s enormous renewable energy potential. For wind power, there are exceptional natural resources in some parts of the country, particularly in Constanța county where Rezolv’s 600MW Dunarea East & West wind farms will be built. But it’s not only along the Black Sea coast. Rezolv’s other onshore wind project in Romania, VIFOR, is in Buzău county, more than 200km inland – where the proximity to the Carpathian Mountains also gives rise to high wind yields.

The solar potential is huge too. Romania joined the International Solar Alliance during COP28. In making the announcement, Energy Minister Sebastian Burduja estimated the country’s technical solar potential at 19.35GW (25.80 TWh), with 18.05GW (24.18 TWh) deemed economically viable under minimum cost scenarios. These are not small numbers, and it’s primarily, obviously, because the whole of South Eastern Europe enjoys plenty of sunshine.

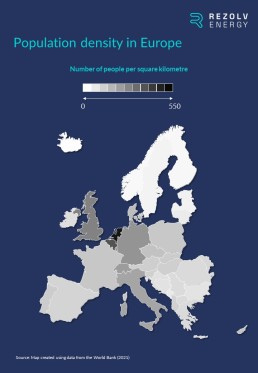

It’s also about available land, though. Very large-scale solar projects like those Rezolv is developing require large, flat sites (as well as good solar irradiation and grid access). Our 229MW St. George project in Bulgaria, for example, will cover 165 hectares. Dama Solar, our 1,044MW solar project in western Romania, will be significantly larger than that.

Sites of that size are clearly not available everywhere, but they are a bit easier to find in Central & South Eastern Europe than some parts of Western Europe – because it is not the most densely populated part of Europe:

Bulgaria: a case study of how broader government priorities are driving the energy transition

Political attitudes in Bulgaria also illustrate the fact that EU targets are not the only driver of change in this region.

Ahead of the unveiling of the EU’s climate target for 2040, 11 member states jointly called on the EU to set “an ambitious climate target for 2040…[which] should be in line with the long-term temperature goal of 1.5°C… The target should also ensure that the EU is fully on track to climate neutrality by 2050 at the latest aiming to achieve negative emissions thereafter.”

Bulgaria was the only Central & Eastern European country in the group of 11 member states that signed that letter. Why Bulgaria?

In part, it is the same factors that are driving the commitment to the energy transition across this region: the need to secure energy supplies, enhance energy independence and drive down energy prices – all of which have become political priorities everywhere since the start of the war in Ukraine.

As in Romania, it is also an acknowledgement of the renewable energy potential in Bulgaria. For example, Bulgaria is on track to achieve its 2030 NECP target for solar power about seven years ahead of schedule, and a recent study from the Centre for the Study of Democracy found that Bulgaria could add between 3.8GW and 4.2GW of wind capacity by 2030, and another 5GW by 2040; offshore wind could add more than 150GW on top of that.

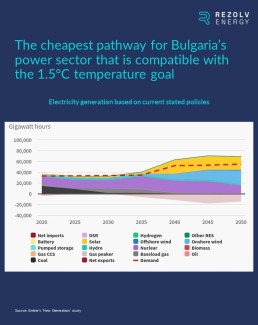

Indeed, based on a study by Ember, the cheapest pathway for Bulgaria’s power sector which is compatible with the 1.5°C temperature goal mentioned in the letter involves the installation of huge amounts of solar and onshore wind:

And it’s not just the EU member states…

We are seeing similar levels of commitment to renewables from non-EU member states in the region as well. For example:

- By 2030, North Macedonia has committed to reducing its net greenhouse gas emissions by 82% compared to 1990 levels. The energy transition will be key to achieving this given how dependent the country has historically been on coal. This commitment is already being backed up by action. Last year, North Macedonia posted 160% growth in new renewables capacity and, at COP28, announced a coal phase-out by 2030.

- Under its draft NECP, Serbia will, by 2030, aim to increase the share of renewables in electricity production to 45.2% and deliver a 40.3% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990.

- Bosnia & Herzegovina aims to deliver a renewable energy share of 43.6% by 2030, most of which will be solar.

Renewables targets will continue to grow – which also represents a big, but not insurmountable challenge

Countries in Central & South Eastern Europe are not purely motivated by the requirement to meet climate targets, but, at the same time, no one is in any doubt that the pressure from Brussels will only continue to increase.

Indeed, on 6 February 2024, the European Commission published a detailed impact assessment on possible pathways to reach the agreed goal of making the EU climate neutral by 2050. Based on the assessment, the Commission expects renewable energy, “complemented by nuclear energy”, to generate over 90% of the electricity consumption in the EU in 2040. A legislative proposal will be made after the European elections, and it will need to be agreed with the European Parliament and member states – but even a watered-down version of this proposal will translate into more ambitious renewable energy targets for every member state.

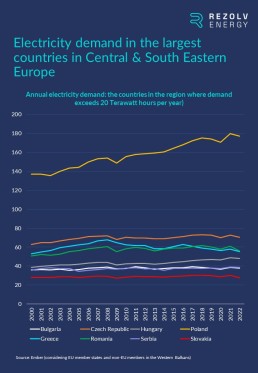

This will be particularly challenging for the largest and most heavily industrialised countries. If you take ‘Central & South Eastern Europe’ to mean the EU member states in the region plus the non-EU countries in the Western Balkans, there are only four countries where annual electricity demand exceeds 50 Terawatts – Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania and Greece:

In these countries, increasing the share of renewable energy is a bigger challenge than it is in smaller countries, because each percentage point represents more gigawatts of renewable capacity.

Summing up: significant progress has been made over the last 12 months, but even more urgency is needed

The political support we are seeing for renewable energy is, of course, not only a consequence of ever-increasing EU targets – but those targets certainly do help focus minds. The truth is that 2030 is not very far away, and large-scale renewable energy projects – the quickest and most effective route to meeting those targets – take time to develop. The progress we have seen across the region over the last 12 months is a great start, but even more urgency is needed.

What is coming up next time?

Some countries’ 2030 targets look tougher to achieve than others’, and next time we are going to be looking at one member state which still has plenty to do: the Czech Republic…

The Czech Republic’s 2030 renewables target will only be achievable with rapid, widespread and coordinated policy change

In the third part of this series, we looked at the 2030 renewable energy and emissions reduction targets that are in place across Central and South Eastern Europe. We concluded that 2030 is not very far away and even more urgency is needed if there is a realistic chance of meeting them.

That statement is true across the board, but there are some countries where the mountain to climb looks particularly steep. The Czech Republic is one of those countries.

The current energy mix in the Czech Republic

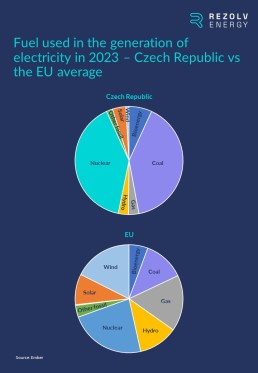

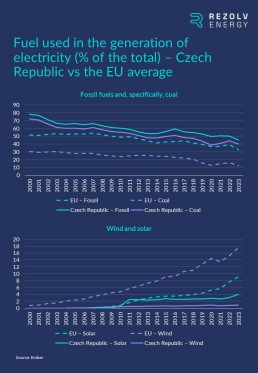

Let’s start by quantifying the scale of the challenge. Last year, 40% of the electricity generated in the Czech Republic was produced from coal, more than three times the EU average:

The contribution from renewable sources – hydro power, bioenergy, wind and solar – represented just under 15% of the total, comfortably the lowest proportion anywhere in the EU:

That share is only four percentage points better than a decade ago, but half of that extra renewable energy capacity has been added in the last 12 months, mostly from rooftop solar:

The 2030 renewables target has been increasing steadily – and is about to go up again

Now consider the target the Czech Republic has set itself for the share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption by 2030. It’s a target which has been steadily increasing:

- Target set in December 2018: 20.8%

This was the figure submitted to the European Commission by the Czech government in the first National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). To put this in context, the EU target was 32% at that point.

- Target set in November 2019: 22%

The final NECP increased the target to 22%, but the European Commission still described that as “unambitious”.

- Target set in October 2023: 30%

The draft updated NECP submitted in October proposed a very significant increase, reflecting the fact that the EU’s overall 2030 target had risen to 42.5%. At the time, the Ministry of Environment clarified that this would mean 10GW of installed capacity from solar and 1.5GW from wind by 2030 – almost five times the amount installed up to that point.

- The revised target which is about to emerge: ?%

We are still waiting for the New State Energy Concept and Climate Protection Policy, but the 30% target is going to increase again. Some reports have recently suggested that it could even go up to 37%, but that feels over-optimistic. 33% seems more likely, but even that would represent a significant increase on October’s revised target.

How will this challenge be met? The three top priorities…

This level of ambition from the government is, of course, very welcome. It reflects a degree of political will to support the energy transition which hasn’t been in place since the ‘solar boom’ of well over a decade ago.

However, no one in the sector is in any doubt about the scale of this challenge. Even the current 30% target represents a doubling of renewables capacity in six years (and, as mentioned, the new target will be even higher than that). Whatever the final number, there is no way that it can be delivered without rapid, bold and comprehensive policy-making.

The government will need to do many things, but based on our experience from across the region, there are three areas that it will need to address with particular urgency:

- Prioritise large-scale renewables projects

There is no prospect of meeting a 30+% renewables target without utility-scale wind and solar projects – which are also proportionately cheaper and deliver the lowest cost of electricity for everyone.

Large projects require space, of course, and there is a common misconception in the Czech Republic that space is one thing the country lacks. This isn’t true. There is plenty of available publicly-owned land that would be suitable for major renewables projects, for example. Up to now, the issue has been a lack of political will, not available land. We are very hopeful that, with the political will now in place, we will start to see progress in this area.

But things will need to move forward very quickly, because large-scale renewables projects take time to develop and build. In the context of major infrastructure development, six years is not a long time.

- Serious investment needs to be made into the grid

Significant investments also need to be made into grid capacity and flexibility to support the volumes of clean power that will be coming onstream. This is well understood and acknowledged within government and across the sector.

The numbers are substantial. The Chairman of the Czech Energy Regulatory Authority (ERÚ) recently estimated the investment needed into the transmission and distribution system at 271 billion crowns (€10.7 billion) by 2030. Not all of that is directly related to the development of green energy, but it is an indication of the kind of money that will need to be found.

Joined up policy-making will be required here too. For example, the windiest areas of the Czech Republic are, mostly, not currently connected to the grid. Decisions over the location of acceleration zones for future renewables projects therefore need to come first, based on which the necessary grid investment plans can be drawn up.

- Introduce a CfD scheme to include larger renewables projects

In October, the EU Council agreed a general approach on a proposal to amend the EU’s electricity market design – which will, in due course, need to be transposed into Czech law. One of the reform’s objectives is to accelerate the deployment of renewables. There are two areas that are particularly important for developers:

First, the reform aims to boost the market for power purchase agreements (PPAs). The European Commission has now been tasked with identifying barriers to cross-border PPAs and with developing best practice and a template contract to accelerate the growth of this market across the EU.

Second, it has been agreed that two-way contracts for difference (CfDs) should, in most cases, be the mandatory model used when public funding is involved to support renewables projects. CfDs are long-term contracts concluded to support investments. They top up the market price when it is low, with the energy producer paying back an amount when the market price is higher than a certain limit. CfD schemes provide predictability and certainty for developers and have been successfully used elsewhere in Europe – for example, in the UK, Germany and Poland. Other countries, including Romania, are about to introduce them.

The Czech Republic has launched auctions on a small scale, but only for biogas plants, small hydropower plants and wind farms. However, the total capacity of power plants that can be entered into auctions is severely limited and there is no auction for solar plants. The Czech government must make a CfD scheme for larger renewable energy plants – both wind and solar – a central pillar of its strategy to accelerate the energy transition.

Let’s not forget the human dimension of the energy transition in the Czech Republic

Targets are important, but they are obviously not the real objective. The real goals are much more meaningful: to secure energy supplies and enhance energy independence, to foster economic competitiveness and to reduce energy bills.

It is also about safeguarding – and, ultimately, improving – the quality of people’s lives.

On one level, that means protecting jobs. To understand this, it’s important to grasp how corporate sustainability targets have evolved. Initially, they mostly focused on reducing the company’s direct greenhouse gas emissions (‘Scope 1’) and emissions caused indirectly through the production of the energy it purchases / uses (‘Scope 2’). Subsequently, in more recent years, hundreds of international companies have gone much further and have also publicly committed to carbon neutrality along the entire production chain (‘Scope 3’ emissions). Scope 3 emissions represent 80% of the total environmental impact for many large companies, and this is becoming a major issue for the Czech Republic, one of the most heavily industrialised countries in Europe, where there are a huge number of small firms in the supply chains of multinational companies with Scope 1-3 net zero targets.

If these businesses want to hold on to those important contracts, they will need to reduce their own emissions – and demonstrate that they have done so. For them, sourcing clean power is not just about sustainability: renewable energy PPAs are going to become vital to their ongoing viability, and therefore to the livelihoods of the people they employ.

The human dimension of the energy transition is bigger than jobs, though – it’s also about public health. In the first two articles, we considered the air pollution problem in Bulgaria and Romania. The issue is not identical in the Czech Republic, but it’s no less important – and it’s worth exploring in some detail because the Czech Republic is a useful case study of why the transition to renewable energy is so important for ordinary people.

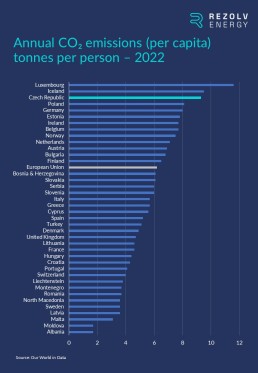

Given how industrial the Czech Republic is, and given the country’s track record on renewables, it’s no surprise that it is, per capita, one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases in Europe:

As we saw in Romania and Bulgaria, this creates pollution which has a direct impact on the health of the general public.

It doesn’t affect every part of the country equally, though. Just under a year ago, the European Environment Agency (EEA) published air quality assessments for 375 cities across the EU. The assessments focused on pollutants deemed to be most harmful to human health – one of which is fine particulate matter (PM2.5). We considered PM2.5 in the first article in this series because exposure at above recommended levels is a leading cause of premature death and disease (particularly stroke, cancer and respiratory disease). In Central & South Eastern Europe, high levels tend to be due primarily to the burning of solid fuels such as coal.

For long-term exposure, the WHO recommends a maximum level of five micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m3) of fine particulate matter. The EEA categorised cities as “poor” where average levels of PM2.5 over the previous two calendar years had been 15-25 μg/m3; “very poor” required average levels above 25 μg/m3.

Only four of the 375 EU cities assessed were evaluated as “very poor”; 77 were categorised as “poor”. When you look closely at those 81 cities, there are five ‘clusters’ where there are at least three “poor” or “very poor” cities in the same regions of the same country. One of these clusters is in the Czech Republic – specifically, the far eastern corner of the country. Out of 15 Czech cities assessed, five had “poor” air quality: Havířov, Ostrava, Olomouc, Zlín and Hradec Králové. Havířov, Ostrava, Olomouc and Zlín – the four most polluted Czech cites assessed – are in Central Moravia and Moravia-Silesia, the country’s easternmost regions (marked light blue on the map below):

Fixing this problem is one of the primary objectives of the clean power transition and should focus minds on the urgency of the challenge.

Summing up: a lot to do in a short period of time

The Czech government’s willingness to keep increasing the 2030 renewables target is an encouraging sign of the political will that now exists to speed up the transition away from fossil fuels, but 2030 is not far away. If the new target – whatever it ends up being – is to be met, policy-makers need to be bold, and to act fast. 2024 will be a crucial year for the energy transition across the whole of Central and South Eastern Europe, but nowhere more so than in the Czech Republic.

What is coming up next time?

Next time, we will be taking a deep-dive into a sector which is not only of vital economic importance to Central and South Eastern Europe, it is also generating much of the demand for renewable energy PPAs: the automotive industry…