In the third part of this series, we looked at the 2030 renewable energy and emissions reduction targets that are in place across Central and South Eastern Europe. We concluded that 2030 is not very far away and even more urgency is needed if there is a realistic chance of meeting them.

That statement is true across the board, but there are some countries where the mountain to climb looks particularly steep. The Czech Republic is one of those countries.

The current energy mix in the Czech Republic

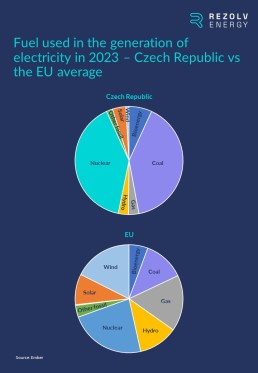

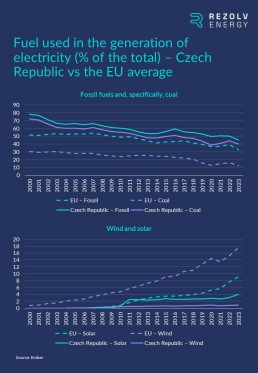

Let’s start by quantifying the scale of the challenge. Last year, 40% of the electricity generated in the Czech Republic was produced from coal, more than three times the EU average:

The contribution from renewable sources – hydro power, bioenergy, wind and solar – represented just under 15% of the total, comfortably the lowest proportion anywhere in the EU:

That share is only four percentage points better than a decade ago, but half of that extra renewable energy capacity has been added in the last 12 months, mostly from rooftop solar:

The 2030 renewables target has been increasing steadily – and is about to go up again

Now consider the target the Czech Republic has set itself for the share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption by 2030. It’s a target which has been steadily increasing:

- Target set in December 2018: 20.8%

This was the figure submitted to the European Commission by the Czech government in the first National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). To put this in context, the EU target was 32% at that point.

- Target set in November 2019: 22%

The final NECP increased the target to 22%, but the European Commission still described that as “unambitious”.

- Target set in October 2023: 30%

The draft updated NECP submitted in October proposed a very significant increase, reflecting the fact that the EU’s overall 2030 target had risen to 42.5%. At the time, the Ministry of Environment clarified that this would mean 10GW of installed capacity from solar and 1.5GW from wind by 2030 – almost five times the amount installed up to that point.

- The revised target which is about to emerge: ?%

We are still waiting for the New State Energy Concept and Climate Protection Policy, but the 30% target is going to increase again. Some reports have recently suggested that it could even go up to 37%, but that feels over-optimistic. 33% seems more likely, but even that would represent a significant increase on October’s revised target.

How will this challenge be met? The three top priorities…

This level of ambition from the government is, of course, very welcome. It reflects a degree of political will to support the energy transition which hasn’t been in place since the ‘solar boom’ of well over a decade ago.

However, no one in the sector is in any doubt about the scale of this challenge. Even the current 30% target represents a doubling of renewables capacity in six years (and, as mentioned, the new target will be even higher than that). Whatever the final number, there is no way that it can be delivered without rapid, bold and comprehensive policy-making.

The government will need to do many things, but based on our experience from across the region, there are three areas that it will need to address with particular urgency:

- Prioritise large-scale renewables projects

There is no prospect of meeting a 30+% renewables target without utility-scale wind and solar projects – which are also proportionately cheaper and deliver the lowest cost of electricity for everyone.

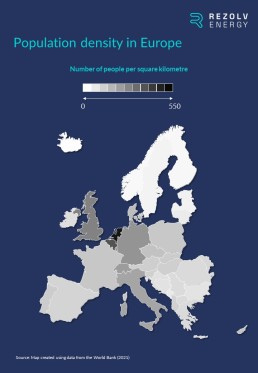

Large projects require space, of course, and there is a common misconception in the Czech Republic that space is one thing the country lacks. This isn’t true. There is plenty of available publicly-owned land that would be suitable for major renewables projects, for example. Up to now, the issue has been a lack of political will, not available land. We are very hopeful that, with the political will now in place, we will start to see progress in this area.

But things will need to move forward very quickly, because large-scale renewables projects take time to develop and build. In the context of major infrastructure development, six years is not a long time.

- Serious investment needs to be made into the grid

Significant investments also need to be made into grid capacity and flexibility to support the volumes of clean power that will be coming onstream. This is well understood and acknowledged within government and across the sector.

The numbers are substantial. The Chairman of the Czech Energy Regulatory Authority (ERÚ) recently estimated the investment needed into the transmission and distribution system at 271 billion crowns (€10.7 billion) by 2030. Not all of that is directly related to the development of green energy, but it is an indication of the kind of money that will need to be found.

Joined up policy-making will be required here too. For example, the windiest areas of the Czech Republic are, mostly, not currently connected to the grid. Decisions over the location of acceleration zones for future renewables projects therefore need to come first, based on which the necessary grid investment plans can be drawn up.

- Introduce a CfD scheme to include larger renewables projects

In October, the EU Council agreed a general approach on a proposal to amend the EU’s electricity market design – which will, in due course, need to be transposed into Czech law. One of the reform’s objectives is to accelerate the deployment of renewables. There are two areas that are particularly important for developers:

First, the reform aims to boost the market for power purchase agreements (PPAs). The European Commission has now been tasked with identifying barriers to cross-border PPAs and with developing best practice and a template contract to accelerate the growth of this market across the EU.

Second, it has been agreed that two-way contracts for difference (CfDs) should, in most cases, be the mandatory model used when public funding is involved to support renewables projects. CfDs are long-term contracts concluded to support investments. They top up the market price when it is low, with the energy producer paying back an amount when the market price is higher than a certain limit. CfD schemes provide predictability and certainty for developers and have been successfully used elsewhere in Europe – for example, in the UK, Germany and Poland. Other countries, including Romania, are about to introduce them.

The Czech Republic has launched auctions on a small scale, but only for biogas plants, small hydropower plants and wind farms. However, the total capacity of power plants that can be entered into auctions is severely limited and there is no auction for solar plants. The Czech government must make a CfD scheme for larger renewable energy plants – both wind and solar – a central pillar of its strategy to accelerate the energy transition.

Let’s not forget the human dimension of the energy transition in the Czech Republic

Targets are important, but they are obviously not the real objective. The real goals are much more meaningful: to secure energy supplies and enhance energy independence, to foster economic competitiveness and to reduce energy bills.

It is also about safeguarding – and, ultimately, improving – the quality of people’s lives.

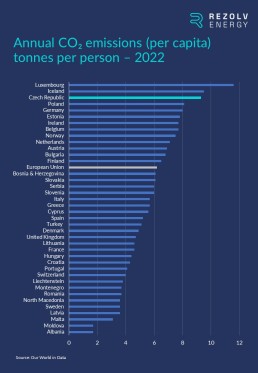

On one level, that means protecting jobs. To understand this, it’s important to grasp how corporate sustainability targets have evolved. Initially, they mostly focused on reducing the company’s direct greenhouse gas emissions (‘Scope 1’) and emissions caused indirectly through the production of the energy it purchases / uses (‘Scope 2’). Subsequently, in more recent years, hundreds of international companies have gone much further and have also publicly committed to carbon neutrality along the entire production chain (‘Scope 3’ emissions). Scope 3 emissions represent 80% of the total environmental impact for many large companies, and this is becoming a major issue for the Czech Republic, one of the most heavily industrialised countries in Europe, where there are a huge number of small firms in the supply chains of multinational companies with Scope 1-3 net zero targets.

If these businesses want to hold on to those important contracts, they will need to reduce their own emissions – and demonstrate that they have done so. For them, sourcing clean power is not just about sustainability: renewable energy PPAs are going to become vital to their ongoing viability, and therefore to the livelihoods of the people they employ.

The human dimension of the energy transition is bigger than jobs, though – it’s also about public health. In the first two articles, we considered the air pollution problem in Bulgaria and Romania. The issue is not identical in the Czech Republic, but it’s no less important – and it’s worth exploring in some detail because the Czech Republic is a useful case study of why the transition to renewable energy is so important for ordinary people.

Given how industrial the Czech Republic is, and given the country’s track record on renewables, it’s no surprise that it is, per capita, one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases in Europe:

As we saw in Romania and Bulgaria, this creates pollution which has a direct impact on the health of the general public.

It doesn’t affect every part of the country equally, though. Just under a year ago, the European Environment Agency (EEA) published air quality assessments for 375 cities across the EU. The assessments focused on pollutants deemed to be most harmful to human health – one of which is fine particulate matter (PM2.5). We considered PM2.5 in the first article in this series because exposure at above recommended levels is a leading cause of premature death and disease (particularly stroke, cancer and respiratory disease). In Central & South Eastern Europe, high levels tend to be due primarily to the burning of solid fuels such as coal.

For long-term exposure, the WHO recommends a maximum level of five micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m3) of fine particulate matter. The EEA categorised cities as “poor” where average levels of PM2.5 over the previous two calendar years had been 15-25 μg/m3; “very poor” required average levels above 25 μg/m3.

Only four of the 375 EU cities assessed were evaluated as “very poor”; 77 were categorised as “poor”. When you look closely at those 81 cities, there are five ‘clusters’ where there are at least three “poor” or “very poor” cities in the same regions of the same country. One of these clusters is in the Czech Republic – specifically, the far eastern corner of the country. Out of 15 Czech cities assessed, five had “poor” air quality: Havířov, Ostrava, Olomouc, Zlín and Hradec Králové. Havířov, Ostrava, Olomouc and Zlín – the four most polluted Czech cites assessed – are in Central Moravia and Moravia-Silesia, the country’s easternmost regions (marked light blue on the map below):

Fixing this problem is one of the primary objectives of the clean power transition and should focus minds on the urgency of the challenge.

Summing up: a lot to do in a short period of time

The Czech government’s willingness to keep increasing the 2030 renewables target is an encouraging sign of the political will that now exists to speed up the transition away from fossil fuels, but 2030 is not far away. If the new target – whatever it ends up being – is to be met, policy-makers need to be bold, and to act fast. 2024 will be a crucial year for the energy transition across the whole of Central and South Eastern Europe, but nowhere more so than in the Czech Republic.

What is coming up next time?

Next time, we will be taking a deep-dive into a sector which is not only of vital economic importance to Central and South Eastern Europe, it is also generating much of the demand for renewable energy PPAs: the automotive industry…

You might also like

8 April 2024

What is driving the interest in PPAs that we are seeing from the automotive sector?

The first few articles in this series included some analyses of individual countries in Central and South Eastern Europe – specifically, Bulgaria, Romania and the Czech Republic.

26 March 2024

Even more urgency is required to meet the 2030 emissions targets in Central & South Eastern Europe

In the first two parts of this series, we explained why Rezolv is investing in Bulgaria and Romania. We focused on the impact that the development of renewable energy will have on emissions and human health. We also outlined why the energy transition is necessary for long-term economic competitiveness.

8 March 2024

Why is Rezolv investing in Romania?

We recently kicked off this series of articles on the clean energy transition in Central & South Eastern Europe by answering the question: why is Rezolv investing in Bulgaria?

8 March 2024

Why is Rezolv investing in Bulgaria?

Rezolv launched 18 months ago to accelerate the energy transition in Central & South Eastern Europe. We already have well over 2GW of clean energy being prepared for construction. This includes St. George, which will become one of Bulgaria’s largest solar plants, and Dama Solar, which will be the largest solar project anywhere in Europe once it is operational. We also have more than 1GW of wind power under construction in Romania.

25 July 2023

Rezolv Energy acquires rights to develop Bulgaria’s largest solar plant

Rezolv Energy, an independent renewable energy producer focused on Central and Southeastern Europe, has acquired the rights to build and operate a 229 MW solar plant in Silistra Municipality in north-eastern Bulgaria. Named ‘St. George’, construction is due to start before the end of this year; the plant is expected to be completed in early 2025. Once constructed, it will be the largest solar plant in Bulgaria.

19 December 2022

Rezolv announces 600MW of new onshore wind capacity in Romania

Rezolv Energy, an independent clean energy power producer focused on sustainable power in Central and South Eastern Europe, has announced its third significant deal since it was established in August 2022.

4 November 2022

Rezolv acquires rights to develop Europe’s largest ever solar photovoltaic plant

Rezolv Energy, an independent clean energy power producer focused on sustainable power in Central and South Eastern Europe, has acquired from the Monsson Group the rights to build and operate a 1,044 MW solar photovoltaic plant in Arad County in western Romania. Once constructed, it is expected to be the largest solar PV plant in Europe.

20 July 2023

Rezolv Energy celebrates first year milestone

We recently gathered in Prague to celebrate a memorable event, marking Rezolv Energy’s one year of success. Today, as we officially turn one, it’s the perfect moment to pause and reflect on our remarkable journey over the past 12 months.

18 August 2022

Rezolv launches to build a new era of sustainable power in Central and South Eastern Europe

Rezolv Energy, the independent clean energy power producer established to build a new era of sustainable power in Central and South Eastern Europe, has officially launched today.